[ad_1]

On 8 September a rare lull descended on British politics as news arrived in London from the Scottish Highlands that Queen Elizabeth was on her deathbed. It was a moment of calm in a year of wild upheaval.

At the end of 2022, in which Britain has had a disastrous mini-budget, two monarchs, three prime ministers and four chancellors, the question arises: apart from extraordinary cast changes – what has really changed?

Rishi Sunak’s arrival at No 10 in October marked the culmination of a period of great turmoil – the fifth prime minister since the 2016 Brexit vote. There were only five premiers since 1979 before that vote.

Sunak’s low-key approach to governance – described by his allies as “show, don’t tell” – has given Britain a break from politics, but many observers believe the events of 2022 will have changed the political landscape in a big way.

“There has been a big change in the position of the parties,” said Anthony Wells, head of political research at YouGov. “It will probably be the year the Tories lose the next election. It is hard to see how they can win a majority next time.”

Sunak hopes he can reap what his colleagues call a “recession dividend” and that competent economic management and recovery from the recession can make the Tories “competitive” ahead of an election expected in late 2024.

But a recent YouGov poll shows just how badly the Tories have suffered in the past year. That gives Labor a 25-point lead over the Conservatives, suggesting that Sunac – grappling with a wave of strikes – has yet to recoup much of the ground lost by his predecessors.

For Wales, a key change in 2022 was that voters looked past the Boris Johnson and Liz Truce premierships, the disastrous management of the economy and the endless infighting, and concluded that the game was up for the Conservatives.

“Voting shows the public Expectation Next time a Labor government,” he said. “In his own way, he drives everything else. They see Keir Starr as the next prime minister. For a Labor leader who has previously struggled to influence the public, that perception is important.

According to political analysts, 2022 also marks a high-water mark for the shock, populist surge that manifested itself in the Brexit vote and saw its culmination under Johnson and Truss – who fought back against the “establishment” that claimed to hold Britain together. tried. back

John McTernan, a political strategist and former adviser to Tony Blair, said: “I think this has been a year of realism and physical facts. Physical facts are quite problematic for populists.

He pointed to the rise of centrist pragmatists such as Joe Biden in the US, Olaf Scholz in Germany and Anthony Albanese in Australia as evidence of a broader trend: “They may be dull, but they have a plan.”

Sunak and Starmer fit the same mold, offering unmistakable stability to voters. “We’ve probably reached the end of the idea that you can govern by changing the prime minister, the chancellor or the home secretary every few months,” McTernan said.

Katie Perrier, a former adviser to Theresa May, agreed: “It’s the end of the populist idea that you can just throw ideas around and not care how you’re going to pay for it.”

McTernan believes that Starmer, “a fixed point in the twisted world of British politics”, will be the ultimate beneficiary of this trend, and Perrier agrees that the profession could feel a shift in the direction of the political winds.

“This was the year when the relationship between business and labor changed dramatically,” she said. This year saw a sharp increase in the number of suits in evidence on the fringes and hotel bars at the opposition party conference in Liverpool.

David Lidington, a former deputy prime minister in May’s government, also believes Britain is moving into a less erratic phase than when Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine began.

Lidington argues that the Ukraine crisis “has clearly had a deep impact in British society”, citing the yellow and blue flags seen across the country and the willingness of British families to host refugees from the conflict.

This renewed focus on the need to defend Western values and security in Europe coincides with a shift in the debate over Brexit in 2022, Lidington argues, which could pave the way for a more harmonious and pragmatic relationship with the EU in the coming years.

“Most people now accept, even though they voted, that Brexit has not been a land of milk and honey,” he said. Lord Michael Heseltine, a former Tory cabinet minister, continued: “There was a moment a few months ago when people started to accept that Brexit was a disaster.”

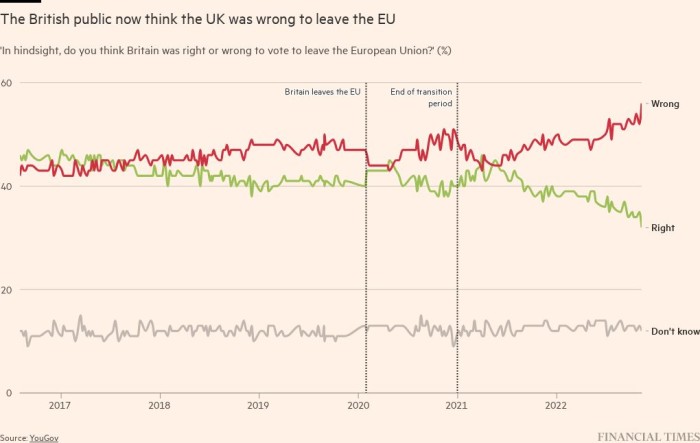

Polls suggest a growing number of people regret the Brexit vote and economic data confirm the blow to the economy, but the fact that none of the main parties want to even discuss rejoining the single market or the European Union itself has taken some of the heat off. is of issue.

Lidington said Johnson’s ouster from No 10 marked a watershed, allowing European leaders to begin trying to repair the damage and build a new partnership in a less toxic environment.

“European politics can now be discussed without reference to 2016,” he said. “He moved on and we moved on.” Lidington says he recently attended a UK-Germany forum where Brexit was “barely mentioned”; Instead the focus was on Ukraine, Russia, climate, energy and China.

The events of 2022 also raised a profound question for Sunak: what are the Conservatives? for? After a decade of anemic growth and increasing demands on public services, Tory prime ministers have been forced to raise taxes to their highest post-war levels and the state has grown.

Johnson and Truce have done their best over the years to blame others for Britain’s plight: the EU, the judiciary, civil servants, Parliament, the BBC, the Treasury, the Bank of England, the people with “North London Town House” and the podcast.

Meanwhile, Truce’s radical tax-cutting and deregulation experiment became a wall of public opposition. In fact public support for striking nurses – two-thirds of voters support their industrial action – suggests that the public favors more investment in the crumbling public sector rather than less.

The simplest free-market ways to boost growth, such as increasing immigration, relaxing planning laws or rejoining the EU’s larger single market, have been rejected by Sunac under pressure from his own MPs.

In fact 2022 proved beyond doubt that there are no quick fixes to Britain’s problems and that the public are tired of being blamed by politicians. Sunak and Starmer will now have to live with that uncomfortable legacy.

[ad_2]

Source link